& Juliet Historical Costume Influences: Part I

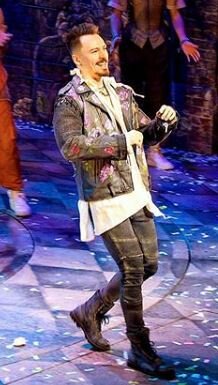

& Juliet is a 2019 musical now up in the West End in London that starts off at the end of Romeo & Juliet. Instead of killing herself, Juliet survives, and runs off to Paris with some friends to avoid being sent to a convent by her parents. Shenanigans ensue. There’s also a frame story about William Shakespeare and his wife, Anne Hathaway (no, not that one) arguing over how to plot out the story. All the songs in the musical are by Max Martin and were previously big pop hits; think “I Want it That Way,” “…One More Time",” “It’s Gonna Be Me, “Blow,” and other songs by Backstreet Boys, Britney Spears, NSync, and other artists.

Credit: Johan Persson

I’m not SUPER familiar with the musical, but I’ve listened to a bit of the soundtrack, have read through the WIkipedia page, and have seen some awesome photos of the costumes, which mash up renaissance and modern elements. So of course, I want to go through and analyze some of the costume elements through the lens of Tudor history. I’m not going to go AS in depth with these costumes as I previously have with Six, because & Juliet has WAY more than six characters and plenty of those characters seem to have several costumes. I’m also sure I won’t be able to get all the costumes, so I’m honestly not going to fuss about it too much.

Although Romeo and Juliet technically takes place in Italy, and most of this musical takes place in France, the costumes seem to be far more English renaissance inspired; there were a lot of similarities in renaissance dress in these three countries, but also some pretty striking differences.

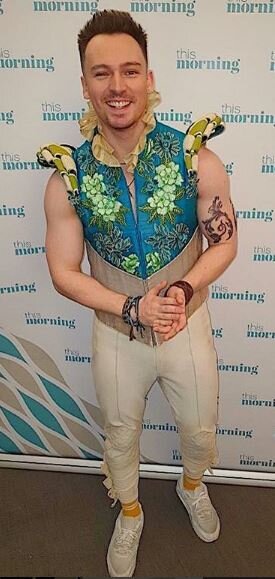

Because there are so many characters and SO many costumes in this show, I’ve had to divide up this post into two to make it more manageable. :) Part two should come out next week, and will focus more on men’s costumes, although a few women and an awesome nonbinary character will also be covered.

(FYI: A fair amount of the explanation of the different elements is borrowed from my previous post on the Tudor fashion elements of the costumes in Six the Musical. )

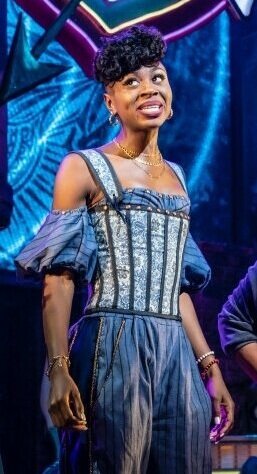

Juliet from &Juliet (Credit: Michael Wharley)

Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I, 1598. Artist Unknown.

Juliet (Miriam-Teak Lee)- As the main character, Juliet has numerous costumes, but at least in the few I’m seeing here, it seems like she usually wears tops that resemble corsets, with the stiffness and lines of boning and/or stays evident, but without lacing. She also sports a lot of wide square necklines, long sleeves, and a fair amount of bling, in the form of necklaces and bracelets. Of interest: the white jacket she wears at the end of the show has little cross hatching and beading details on it that actually somewhat resemble Elizabeth I’s sleeves in the portrait I’ve included above.

Several of her skirts are very poufy, resembling both the volume of Tudor skirts. Her blue outfit also features big poufy pants, which are similar to some men’s styles of the time. It looks like she’s wearing similar pants in the photograph at the top of this post, only in pink, but I couldn’t find any close up pictures of this costume to confirm it.

It looks like almost all the shoes used in the musical are very deliberately worn and a little ragged around the edges, with a few specific exceptions. I wonder what the meaning of that is.

Understudy Grace Mouat on as Juliet

A great farthingale. Elizabeth I, "The Ditchley Portrait", c.1592. By Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger

Spanish farthingales. Retable of St. John the Baptist, ~1470-1480, by Pedro García de Benabarre.

Details of paintings from (starting top left, going clockwise): Anne of Cleves, Jane Seymour, Catherine Howard, Elizabeth I, Mary I, and Catherine Parr.

Poufy Skirts - The voluminous skirts Juliet wears in her pink and white outfits seem inspired by Tudor skirts, which were of a decent size. Tudor skirts weren’t even close to the biggest skirts in history (that honor belongs to the French court dresses of the 1760s-70s-ish, which often featured panniers, structured undergarments which stretched the skirts out horizontally by several feet) but they were still rather large at times! That’s generally due to the farthingale, but bum rolls contributed a bit as well (I’ll talk about bum rolls later in this post).

Catherine of Aragon brought the Spanish farthingale (hoop skirt) fashion into England when she married Prince Arthur (Henry VIII’s older brother, who died less than a year into their marriage). These early farthingales were usually made with wood; the name actually derives from the Spanish word verdugo, which means “green wood.” French farthingales, which started showing up in England in the 1520s, possibly due to Anne Boleyn’s influence on fashion, were often stuffed with cotton and stiffened with hoops of wood, reed, or whalebone. Although we know the materials that made up these undergarments, as tailor’s receipts and such have survived, we don’t know exactly what they look like, because, as an undergarment, they weren’t visible in paintings (boudoir art that showed women in their underwear wouldn’t be culturally acceptable in England for a LONG time).

Later, by the time of Elizabeth I, these French farthingales became “great farthingales,” which ballooned the skirts out all around. You can see that in the portrait of Queen Elizabeth in the previous section. The classic Tudor silhouette you see in portraits, showing an inverted triangle waist dropping down into a voluminous skirt, is created by farthingales.Wide square necklines - Wide and low cut square necklines were very big in women’s fashion under Henry VIII, from about 1500-1550.

Bling- In Tudor times, noble ladies would often wear lots of rings, bracelets, and several necklaces. You can see this in their portraits.

Sleeves - All Tudor women would have worn long sleeves coming down at least to the wrist, and sometimes below that. These often were very voluminous at the top.

Credit: Johan Persson

Henry IV, King of France, by Frans Pourbus the Younger

Elizabeth I’s effigy corset and examples of boning in modern recreations

Boning/Stays - The supportive looking lines in Juliet’s blue top refer to boning within dresses and supportive stays. These aren’t overtly Tudor, as they’re generally associated with later time periods, and I unfortunately don’t have any painting references for this because they were explicitly /underwear/ and not something that would show up in art, but we do know that whalebone was used for support in women’s garments at least by the time of Elizabeth I’s death, as her effigy wore a corset containing whalebone. I’ve included a picture of the effigy corset and a few pictures of historical reproduction corsets so you can see what I mean.

Poufy pants - These are actually called trunkhose. They were voluminous breeches that usually ran from the waist to the middle of the thigh, and were worn with tight fitting hose under them. They were worn by men in the 16th and 17th centuries. They kind of look like onions, right?

I’m trying to pin down more information about when exactly men started wearing trunkhose and why (if there is ever a reason for fashion), but unfortunately, I’ve found it’s much more difficult to find information on men’s renaissance fashion than women’s (see: reasons I’m putting off the second post of this series until next week).

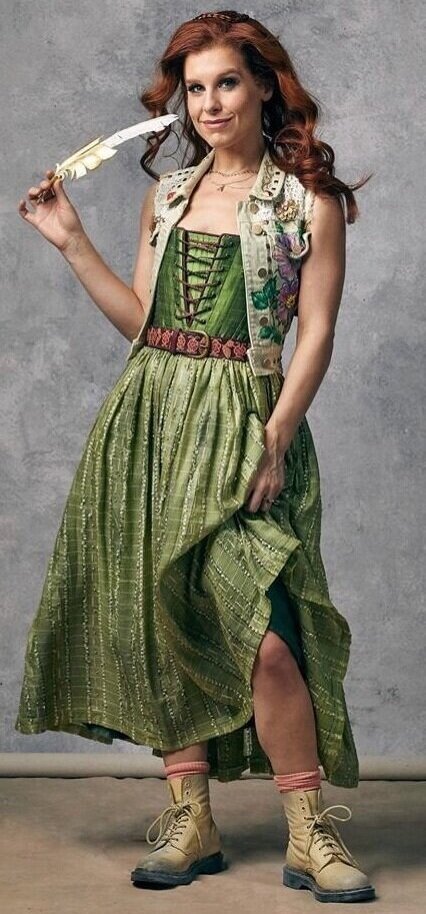

Anne Hathaway (Credit: Michael Wharely)

A 1708 drawing that purportedly shows Anne Hathaway, William Shakespeare’s wife.

Anne Hathaway (Cassidy Janson) - This outfit features cross-lacing, a corset style top that appears to have the stiffness and structure of boning/stays, a wide, square neckline, and a belt at the waist, all elements commonly seen in noble lady fashions during Henry’s reign.

Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk

The vest is interesting. In terms of Tudor fashion, it most resembles an overcoat, which was normally worn by men (see the portrait of Charles Brandon to the right), and is covered with gorgeous colorful embroidery. I’m guessing this refers to her role in the play, in which she takes some of the story-telling power away from her husband.

I’ve included a purported portrait of the historical Anne Hathaway for reference, but it’s basically just her face and a ruff. I don’t think there’s much inspiration to be found here.

Cross lacing detail from a portrait

Cross-Lacing - The “corset” top here is cross-laced, looking like a shoelace tie. This is pretty much what you see at every renaissance faire. In reality though, Tudor gowns were generally spiral laced or ladder laced rather than cross laced (Xes) You can see what I mean in the collection of painting references; all of these show spiral lacing or ladder lacing except for one Italian painting, which shows Xes which are almost certainly more decorative than practical. The other forms of lacing are simply more supportive and adjustable, which is the entire idea behind having lacings in an outfit anyway, after all.

Embroidery - Since almost every young girl was taught to work with a needle, and pretty much every noble lady could embroider, embroidery was very commonly seen in the clothing of nobles. You can see many different examples in the portraits I’ve shared throughout this post.

There were sumptuary laws that restricted what color and type of clothing and trims could be worn by people of various ranks; embroidery was pretty much only allowed for nobles or knights, so it’s questionable whether the historical Anne Hathaway would have been allowed to wear embroidery, as Shakespeare was neither a nobleman nor a knight. However, sumptuary laws were relaxed onstage, and actors could wear clothing that they’d be banned from wearing otherwise, as long as they were performing in a play at the time.

Angelique (Credit: Michael Wharely)

Peasants dancing

Angelique, Juliet’s nurse (Melanie La Barrie) - This honestly looks like the most renaissance costume in the show, complete with a fanny pack resembling a belt and purse and a hair covering. This is a very standard outfit for a female peasant, featuring a woolen undershirt, and a matching skirt and corset style top (with more of that cross lacing). In actuality, the entire orange layer would probably be a single dress, known as a kirtle, which commonly featured square-necks and came down to the ankles.

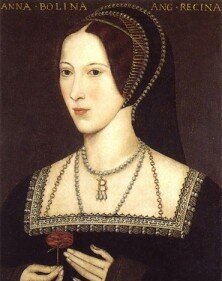

Details from portraits, showing the gable hood of Catherine of Aragon, the French hood of Anne Boleyn, and Catherine Parr’s feathered hat.

Belt and Purse - The fanny pack is a wonderful little touch, as people generally did wear purses on their belts.

Hair Covering - Angelique also is sporting a hair covering here; historically, almost everyone would be wearing a hat or hair covering of some sort (ignore the hair in The Tudors and The White Queen y'all, it's just...hilariously wrong). Famous hats included the Gable hood (seen on Catherine of Aragon and Jane Seymour) and the French hood (popularized by Anne Boleyn and seen in her portrait and in Katherine Howard's supposed portrait). Women even started wearing male hat styles at times, as seen in Catherine Parr’s portrait.

Elisabeth of Austria by Francois Clouet, ca. 1571

Portrait of a Woman, anonymous, 1525-1549

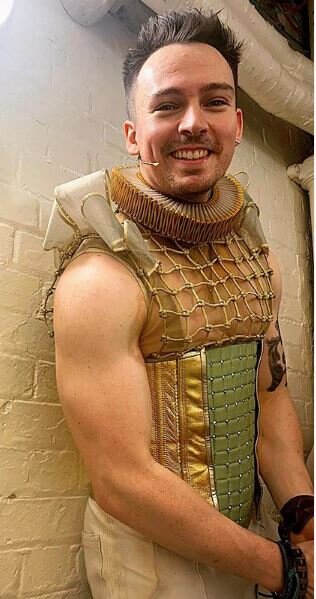

Judith (Grace Mouat)- This costume features numerous Tudor costume elements, including a ruff, white cross hatched sleeves, a double layered skirt rendered in rich orange and reddish orange colors and decorated with copious embroidery, and cross lacing in her leg warmers. I found the Elisabeth of Austria portrait above to demonstrate the sleeves but wow, this costume might actually be totally inspired by it? The color scheme and collar set up is very similar. The anonymous portrait below demonstrates a mesh look more clearly though.

Ruffs - Neck ruffs like this ARE Tudor and specifically, Elizabethan (as opposed to the previously discussed square necklines, which were very Henrican). You didn’t really see them until the 1560s. Keep in mind: Henry VIII died in 1547, his son Edward VI ruled from 1547-1553, his daughter Mary I ruled from 1553-1558, and his younger daughter Elizabeth I ruled from 1558-1603; William Shakespeare lived from 1564-1616 and was active as a playwright probably from the mid-1580s to 1613.

Ruffs were made of fabric, usually cambric but sometimes lace (particularly if you were rich) and were later stiffened with starch imported from continental Europe (think around the Netherlands). They were separate pieces so you could wear a ruff with multiple different outfits, and specifically over the high necklines common to Elizabeth I’s reign. They started out pretty small, but once starch was discovered, ruffs became larger and larger, sometimes up to a foot wide. Really big ruffs had a wire frame to support them.

Fun fact: Apparently ruffs are still part of the ceremonial garments for the Church of Denmark!Double layer skirt - There were lots of layers to women’s garments at this time and often, an over dress, shirt, and skirt were all visible.

Lucy

Katherine Parr, ~1545, by Master John.

Nell

From left, going clockwise: details of paintings of Catherine Parr , Mary I, another of Catherine Parr, and Princess Elizabeth.

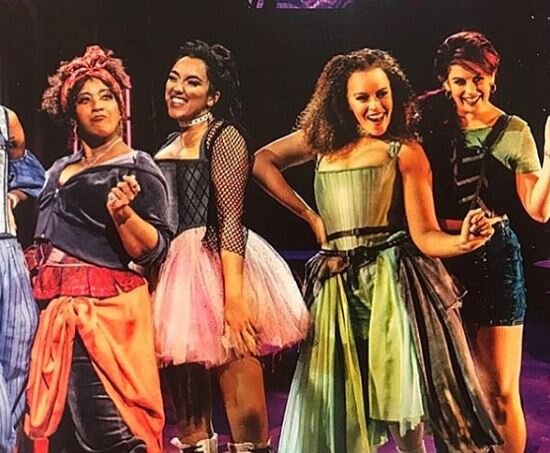

Lucy (Danielle Fiamanya) - This costume includes split skirts worn with a bum roll, boning/stay type elements in the top, and a tied ribbon choker necklace.

Bum Roll - Roll farthingales, or “bum rolls” were padded rolls covered in cotton fabric. They sometimes included wiring. The roll would be placed around the hips and under the kirtle. The one shown in Lucy’s costume appears to be a demi-roll, since it is clearly defined under the skirt but doesn’t completely encircle the body.

Nell (Jocasta Almgill) - This outfit is so fun. Tudor elements include her hair covering (which vaguely resembles a French hood in shape), the boning/stays, the splitskirt layered over denim shorts, and stockings. I can’t quite tell, but it looks like the t-shirt over the outfit has some sort of writing on it? Does anyone know what this is?

Split skirts - Nell’s and Lucy’s costumes both evoke the look of a classic Tudor dress under Henry VIII, in which a kirtle (underdress) was layered under a contrasting overdress. You can see this demonstrated at right, which includes details from portraits of Mary I, Princess Elizabeth.

Susanna

Anne Boleyn, late 16th century, based on a ~1533-1536 work, by an Unknown English artist.

From left, going clockwise: details of paintings of a young Catherine of Aragon, Jane Seymour, Catherine Howard, and Anne of Cleves.

Susanna (Kerrin Orville) - Here you’ve got boning/stay elements, a top that vaguely looks like an overdress, a belt, layers of a skirt over shorts, a wide square neckline, and a choker necklace.

Chokers - Chokers were super popular in renaissance times! You can see several examples in portraits I’ve shared throughout this post. Even the famous “B” necklace from Anne Boleyn’s portrait is a choker.

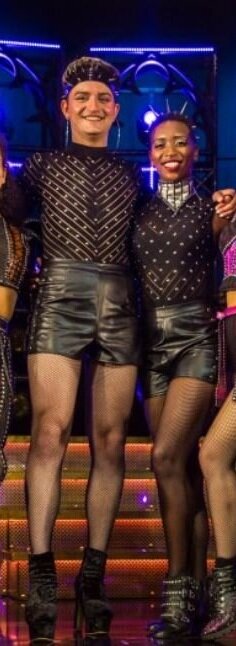

I don’t have the time to analyze every single costume in the show, and since I haven’t seen the show and don’t have plans to go to London any time soon, I don’t have any way to check if I found all the costumes or not. But I’ve put together a gallery from various photos I can find on Instagram of other costumes anyway; look at how gorgeous they are!