& Juliet Historical Costume Influences: Part 2

Part 1 of this series is up here!

& Juliet is a 2019 musical now up in the West End in London that starts off at the end of Romeo & Juliet. Instead of killing herself, Juliet survives, and runs off to Paris with some friends to avoid being sent to a convent by her parents. Shenanigans ensue. There’s also a frame story about William Shakespeare and his wife, Anne Hathaway (no, not that one) arguing over how to plot out the story. All the songs in the musical are by Max Martin and were previously big pop hits; think “I Want it That Way,” “…One More Time",” “It’s Gonna Be Me, “Blow,” and other songs by Backstreet Boys, Britney Spears, NSync, and several other artists.

I’m not SUPER familiar with the musical, but I’ve listened to a bit of the soundtrack, have read through the WIkipedia page, and have seen some awesome photos of the costumes, which mash up renaissance and modern elements. So of course, I want to go through and analyze some of the costume elements through the lens of Tudor history. I’m not going to go AS in depth with these costumes as I previously have with Six, because & Juliet has WAY more than six characters and plenty of those characters seem to have several costumes. I’m also sure I won’t be able to get all the costumes, so I’m honestly not going to fuss about it too much.

Although Romeo and Juliet technically takes place in Italy, and most of this musical takes place in France, the costumes seem to be far more English renaissance inspired; there were a lot of similarities in renaissance dress in these three countries, but also some pretty striking differences.

FYI: A fair amount of the explanation of the different elements is borrowed from my previous post on the Tudor fashion elements of the costumes in Six the Musical.

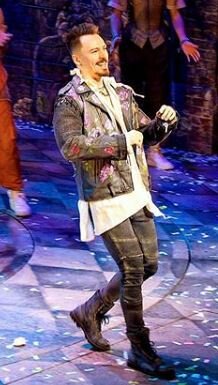

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare

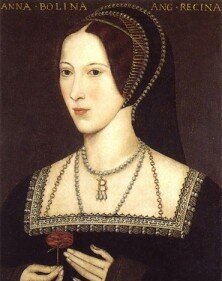

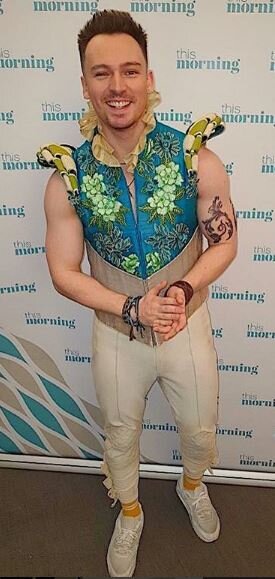

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leceister

William Shakespeare (Oliver Tompsett) - Will’s wearing an undershirt, a vest with a high collar and some very distinct diagonal line cuts, and slim cut jeans that resemble Tudor hose. It’s all rendered in a very Tudor color scheme. Because Shakespeare was an actual historical figure and we have SOME portraits that purport to be of him, it’s possible that this costume was loosely based on one of them. This is one of the more famous ones, and it certainly looks like there’s some inspiration - the coloring in the costume vest and shoes is similar to the mustard yellow background of the Chandos portrait. the white under tunic also looks pretty similar. He’s also sporting a beard.

As you can see in the portrait of Robert Dudley (Elizabeth I’s favorite), high collars and diagonal lines, and vests with cap sleeves were all commonly seen in Elizabethan fashion. Shakespeare was an active playwright from at least 1585-1613 and died in 1616. Elizabeth was on the throne from 1558-1603, after which time her first cousin twice removed (the great-grandson of her father Henry VIII’s sister Margaret Tudor) , James, became king of England.

This peasant man is wearing hose that are much baggier than those often seen worn by nobles. Trevilian Miscellany, 1602

Hose - Hose were undergarments covering the full length of the legs for a long time. They were probably made to measure by a hosier and cut on the bias to allow the cloth to stretch. However, in the last quarter of the 15th century, fashionable young men in Italy began to omit the gown or tunic traditionally worn over their hose and doublet. This resulted in the development of the codpiece (discussed further down in the post), as previously, each leg of a man’s hose was separate, as it wasn’t visible, and thus left a gap around the crotch area.

Tight fitting hose and doublets that rose above the hips were popular in England in the first half of the 16th century, although the trend quickly moved toward wearing gowns over the doublet and tunic, which revealed the hose and codpiece beneath those layers, but widened the figure into the fashionable male silhouette inspired by Henry VIII’s own generous size.

Hose was sometimes very tight and close fitting, particularly among upper classes that could afford the type of cloth and tailoring required for such looks, but lower class folks often had baggier hose.Beards- Beards were unfashionable for a long time in England, as Henry V chose to go beardless and EVERYONE wanted to be like Henry V. His son, Henry VI, his son’s successor, Edward IV, HIS successor, Richard III, and HIS successor, Henry VII allllll went beardless.

However, Henry VIII brought the beard back into vogue during his reign. He was clean-shaven for the first two decades or so of his reign, but grew a beard after promising the French that he would not shave his beard until he met the King of France at the Field of Cloth of Gold; the King of France made the same vow (Fun story: Catherine of Aragon hated her husband’s beard enough that he eventually shaved it off, which caused something of a diplomatic debacle, until his French ambassador, a charming fellow named Thomas Boleyn, managed to persuade the French King’s mother that “Love is not in the beards, but in the hearts.”)

Apparently even after the field of cloth of gold, Henry liked his beard enough to keep it, and sports it in his most famous portrait. It became fashionable again, and was VERY popular by the time of his daughter Elizabeth’s reign, during which Shakespeare lived. In fact, beards were cut in numerous different styles, which apparently were sometimes distinct enough for them to signify a specific profession (which must have been very useful for actors on stage - based on the styling of their beard, audiences could recognize them as a bishop, clown or what have you!). They were often styled with starch, which was a similarly popular fashion element for ruffs, which are discussed later in this post.

Romeo

Henry VIII. In case you didn’t know that.

I don’t know for sure, as I haven’t seen the show, but I believe this is Juliet’s dress when she finds Romeo’s dead body. At this point, her pink flower and color scheme match Romeo’s jacket.

Romeo (Jordan Luke Gage) - Believe it or not, Romeo’s outfit follows a lot of the same guidelines as Henry VIII’s outfit in his famous portrait. He’s got an undershirt, an overshirt, an overcoat, tightly fitting jeans resembling hose with zipper details that resemble garters and/or embroidery details, decorative (and detached) sleeves, ruffled shirt cuffs, and several necklaces and rings. He’s also sporting nice black boots with leggings tucked into them (that look BARELY used compared to most character’s very scuffed up shoes. I HAVE to figure out the meaning of these shoes - does it indicate life experience?).

He wears a pink shirt and his coat is covered in pink roses, probably representing his typically romantic worldview. His outfit also matches Juliet’s dress at the beginning. It looks like there’s writing on his jacket as well? This could be referring to his role as a play character.

Undershirt/overshirt - I didn’t discuss this in my first post, really, but undershirts in Tudor times were really a practical solution to the difficulty of washing a lot of the finer clothes of the day. The thin shirt by your skin absorbed up most of your sweat and was significantly easier to launder.

Detached sleeves - Detached sleeves that could be removed or attached by lacings to the body of a shirt or dress were common in both men and women’s garments, as it gave wearers options for changing up their style. The detached sleeve really began to develop in the 1480s and peaked around 1525 (according to “What People Wore When”).

Garters - The zipper details on Romeo’s pants could be meant to resemble garters, which you can see in Henry VIII’s portrait at right. Garters were worn by men and women to hold up hose, as elastic hadn’t been invented yet. These could be made of leather, fabric, or ribbon and were often tied below the knee to support the hose. You can see Henry VIII’s garters in his portrait above.

Embroidery - Since almost every young girl in Tudor Society was taught to work with a needle, and pretty much every noble lady could embroider, embroidery was very commonly seen in the clothing of nobles. You can see many different examples in the portraits I’ve shared throughout this post.

There were sumptuary laws that restricted what color and type of clothing and trims could be worn by people of various ranks; embroidery was pretty much only allowed for nobles or knights (were the Montagues nobles in Romeo and Juliet? perhaps. But the actor playing Romeo in Elizabethan England sure wouldn’t have been). However, sumptuary laws were relaxed onstage, and actors could wear clothing that they’d be banned from wearing otherwise, as long as they were performing in a play at the time.Bling - Men wore just as much bling as women did in Tudor times! Here, you can see Romeo sporting a necklace and at least one ring, maybe more (it’s hard to see). In his portrait, you can see that Henry VIII is wearing at least two necklaces (the large one looks like his collar of office) and three rings, as well as jewels incorporated into this hat decoration, the buttons and decorations on his sleeves, and even in his knife’s scabbard. Records indicate that Henry VIII sometimes wore a ring on every finger.

Although jewels in jewelry was generally confined to noble classes, as these were quite costly, lower classes still commonly wore jewelry made of glass, bone, or wood. Gold jewelry was apparently popular with all of the classes as well.

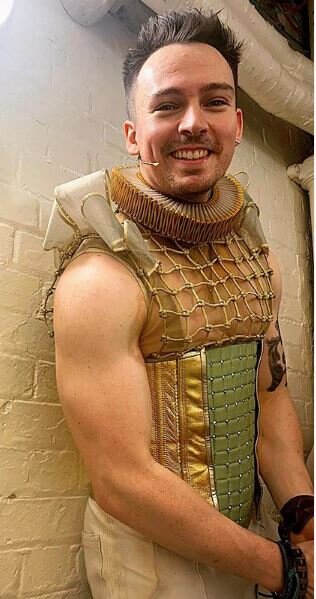

Lance

Charles IX of France, who reigned from 1560-1574. By François Clouet.

Lance, the King of France (David Bedella) - Lances’ outfit is actually very close to renaissance fashion except for the jeans. He’s sporting an under shirt, a blue doublet festooned with gold chains, and a heavily embroidered cape. His slim cut jeans closely resemble hose. His blue boots are totally glorious (and entirely unscuffed) and look like they’ve got some sort of delicate design over them.

It’s interesting that he and Angelique are the characters who sport the most Tudor fashions, and it looks like they might end up together in the end.

Cloak/cape - Although overcoats were more popular in Henry VIII’s time, short capes that fell to the hips were fashionable in the later part of the 1500s. The cape (and shirt) that Lance wears in the musical resembles the one in the portrait of Charles IX I’ve included on the right, which is similarly festooned with intricate detailing. The one Lance is wearing is worn over the shoulder and held in place by the hand, serving both a practical and a fashionable purpose.

Blue - Both Lance and Francois are wearing blue, which is a traditional symbol of France that’s been found in French flags and heraldry for centuries.

Boots - In the renaissance, men and women wore similar flat shoes with rounded toes. The shoes were often made of silk, velvet, or leather. Duckbill shoes were pretty fashionable in Henry VIII’s time, as you can see in his portrait above, but were out of fashion by Elizabethan times and were back to narrow toes then.

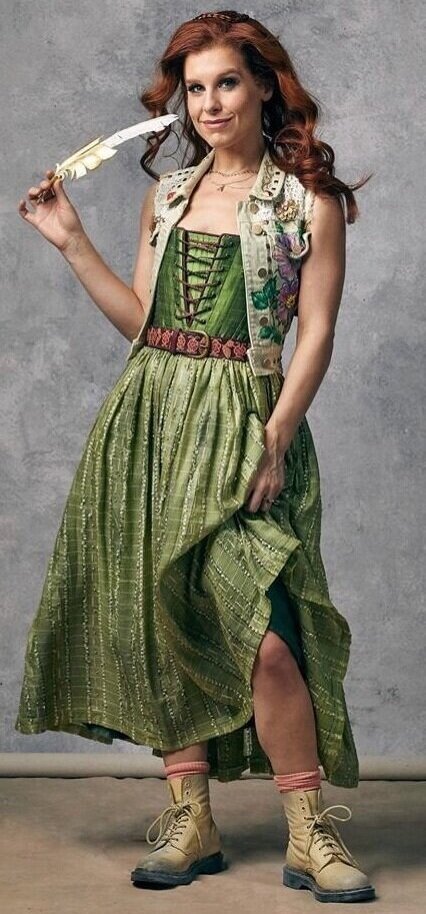

Francois

Louis IX of France, who reigned from 1226-1270.

Francois, the Prince of France (Tim Mahendran) - Francois is wearing a short sleeved undershirt, a long robe covered in fleur-de-lis, and slim cut jeans which resemble hose. Everything is blue, naturally, because France.

Fleur-de-lis - The flower symbol known as the fleur-de-lis, referring to the flowers growing by the Lys river in France, is very old, and has appeared in artwork dating back to ancient times. The fleur-de-lis was stamped on Gaulish coins from around 100-50 B.C. and has been used as a symbol by all the Christian Frankish kings.

Long Robe - Francois’s fleur-de-lis covered blue vest looks like it was perhaps inspired by French ceremonial robes and fabrics worn by MANY monarchs (seriously, I found so many paintings of French monarchs wearing blue fabric covered with fleur-des-lis, although those were usually yellow, instead of Francois’ light blue); I thought this stained glass window of Louis IX had the most similar positioning of fleur des lis on the fabric to the & Juliet costume.

This type of longer surcoat (outer tunic), which fits closely to the body, but has no defined waist, and goes down to the hips, was seen more in the early 15th century and wasn’t really very fashionable by Tudor times. In Henrican times, surcoats were much wider than this, and in Elizabethan times, they generally had a much more defined waist. That’s another reason I think this costume was really based off of depictions of French royal ceremonial wear, rather than portraits, which reflected modern fashion more often.

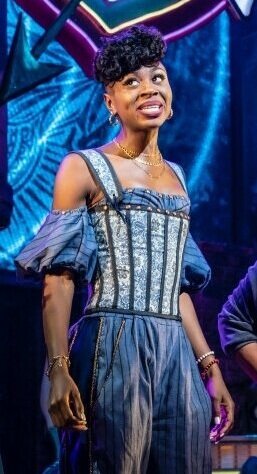

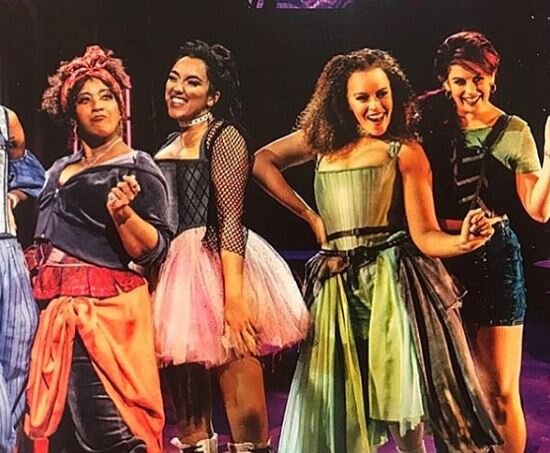

Imogen

Augustine

May

Imogen (Rhian Duncan) - Imogen wears clothes that are inspired by both female and male Tudor fashions. Her top clearly is based on a corset with stays, with an undershirt under it, and her pants are based on some of the baggier hose variations, with decorative lines down the front and studded designs.

I’ve noticed that the characters in &Juliet that are less likely to be nobles seem to wear much baggier pants than the royals. You can see this in nearly all the rest of the photos in this post.

Boning/Stays - The supportive looking lines in Imogen’s top refer to boning within dresses and supportive stays. These aren’t overtly Tudor, as they’re generally associated with later time periods, and I unfortunately don’t have any painting references for this because they were explicitly /underwear/ and not something that would show up in art, but we do know that whalebone was used for support in women’s garments at least by the time of Elizabeth I’s death, as her effigy wore a corset containing whalebone.

These diagonal lines on the costumes help evoke the ideal Tudor silhouette of a inverted triangular waist (see the portrait at right for an example. You can also see this in many portraits of Elizabeth I) without actually requiring the actor to wear such a body shaping garment.Studs - The metal studs in the pants resemble those seen in Brigandines, a type of historical armor. Brigandines are made of heavy cloth or leather with steel plates riveted to it, and are pretty distinctive, with visible metal studs on the front.

Augustine (Antoine Murray-Straughan) is wearing a quilted vest with baggy pants resembling hose.

Quilted vest - Quilted cloth was actually commonly used by soldiers, either alone or under armor. One type of Medieval European armor called the jack of plates (or coat of plates) actually looked like a quilt, but had small iron plates sewn between layers of felt and canvas. Although jack of plates were used in Medieval times, they were worn through the 16th century.

If you’ve read my Ladies in Waiting of Six post, you may notice that this garment sounds similar to the brigandine I described there. The main difference is that the plates in a brigandine were riveted into place between the cloth layers, rather than sewn, so metal studs were generally visible on the outside. A jack of plates has its metal bits sewn between cloth, so you’re not going to see metal on the outside of that.

May, Juliet’s non-binary friend (Arun Blair-Mangat) wears what looks like a single piece jumpsuit with a quilted design all over it and a leather belt over it. I’m pretty sure jumpsuits weren’t a thing back then, but the shapes of the clothing are very similar to some of the undershirts and baggy hose that I’ve talked about elsewhere in the post. This outfit is actually very similar to renaissance male clothing, but the color is a bit more feminine to modern eyes. It’s a very unusual color for Tudor times, as you usually don’t see purple clothes at all in paintings from back then (I looked. a lot), and definitely not this light lavender look. It’s so pretty!

It also looks like May’s wearing a flower/butterfly crown. Although you see flower crowns everywhere at renaissance festivals, I couldn’t find any in actual paintings from that time period. Flower crowns have such a long history in multiple cultures though, that I’d be surprised if they weren’t worn occasionally, probably by peasants for various festivals and such.

I don’t know much about non-binary/transgender people in Tudor times, but I do want to research it and write a blog post about it in the future!

Belt - Both men and women commonly wore belts just as a practical element, as they could hang purses, knifes, or other useful items from them.

Henry

Kempe

Henry (Alex Tranter) - This costume features super tight pants with slashing like details on them, an um, emphasized crotch that might be a reference to a codpiece, a leather-ish cropped vest and belt with cool cross-hatching details, and ruffling around the neck that looks like it’s meant to resemble a ruff.

Split Ruff- This looks a bit like the ruff in Robert Dudley’s portrait further up in the post, in the section on Shakespeare. The ruff began as an attached trimming to the high collar of a mid-16th century shirt or chemise (which looks to be the case here), but over time, developed into a separate accessory that could be worn with various different outfits. The discovery of starch in the 1560s really influenced the growth of ruffs, both in size and popularity. A large split ruff like the one in the portrait above became popular in the 1590s, when Elizabeth I was spotted wearing such looks. The ruff may also have been wired, to keep it standing up.

Slashing- Slashes are slits of different lengths cut into a garment in a specific pattern, for decorative purposes. The style became popular in northern Europe around the end of the 15th century.

Codpieces- As mentioned earlier, the codpiece was developed once doublet lengths went to above the waist, as the separate legs of men’s hose previously left a gap there that had to be covered. This started out as a very practical cloth covering but it become larger, more emphasized, and more decorated over time. Boning and padding was added and sometimes they were even large enough to hold money or jewels, which may have led to the saying “the family jewels.” You can see examples of them to the right and in the portrait of Henry VIII up earlier in the post. Their popularity may have also been influenced by the spread of syphilis; a codpiece allows for lots of room for bandages and ointments and such.

The name, funnily enough, comes from the middle English for both “scrotum” and “bag.” They were very popular under Henry VIII but eventually declined in popularity under his daughter Elizabeth I.

Renaissance gentleman in armour, unknown, circle of Peter Pourbus

Kempe (Kieran Lai) - I haven’t seen the play so I don’t know a lot of the details, but this character’s name, at least, is clearly based off of Will Kempe, an English comic actor who worked with Shakespeare. He was fairly famous at the time and in 1600, actually morris danced from London to Norwich (~100 miles); this took him nine days spread out over a few weeks. This drawing on the right shows him performing this stunt. The character Kempe’s costume doesn’t seem to owe much to this historical drawing except perhaps in the structure of the pants, which are tight at the bottom and baggier at the top, allowing for free movement during dancing.

His studded vest has some of the jack of plate elements I was talking about earlier and his pants look inspired by baggy hose.

Benvolio

Sly

Benvolio (Kirstie Skiv) wears fingerless gloves, a hat, a spiky leather vest over a longer shirt, and sweat pants resembling hose.

Hat - Historically, almost everyone would be wearing a hat or hair covering of some sort. You just had your hair covered most of the time, that’s just…what you did. Benvolio’s one of the only characters who has a hat.

Gloves - Gloves were very popular among the rich in Tudor England, as they demonstrated that the wearers weren’t doing any manual work. They were shown in a lot of portraits and were often simply held by the sitters instead of being worn (you can see that in the portrait on the left below this text). Tudor England was really stinky, so gloves were often scented. In addition, this may be a stretch of a reference, but William Shakespeare’s father John Shakespeare WAS a glover, who made leather from animal hides and then into gloves.

Portrait of a Gentleman, Unknown

Portrait of a Gentleman of the English Court, by Hans Eworth

Henry IV, King of France, 1610, by France Pourbus the Younger

Sly (Ivan DeFreitas as Sly) wears super voluminous sleeves with ties in various places and super baggy pants that resemble baggy hose and/or trunkhose, with a belt.

Princess Jasmine sleeves - This costume features poufy sleeves with various ties on them. I don’t know how to describe these sleeves except they kind of look like Princess Jasmine’s hair. Since I don’t know how to describe them, I can’t really google them and figure out what they’re called, but I DID find this portrait above in the middle showing a Tudor era gentleman with very similarly shaped sleeves.

Poufy pants - Sly’s pants are so poufy that they almost look like the trunkhose that Juliet wears (see part 1 of this). As a reminder, those were voluminous breeches that usually ran from the waist to the middle of the thigh, and were worn with tight fitting hose under them.